Long thought to operate at the physical limits of sensing, E. coli chemotaxis turns out to be constrained not by fundamental physics, but by cells’ own noisy signal processing. Yale researchers along with researchers at the Flatiron Institute, Academica Sinica and the National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (Taiwan) have recently published their research in Nature Physics.

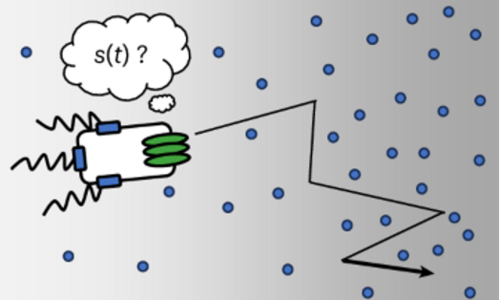

How accurately can organisms sense their environments, and what ultimately limits this accuracy? This paper by Henry H. Mattingly (Associate Research Scientist, Flatiron Institute), Keita Kamino (Assistant Research Fellow, Academica Sinica, Taiwan), Jude Ong (Former Undergraduate Student, Yale University now a Postgraduate Researcher at NIH), Rafaela Kottou (Undergraduate Student, Yale University), Thierry Emonet (Lewis B. Cullman Professor of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology and Professor of Physics, Yale University), and Ben Machta (Associate Professor of Physics, Yale University) revisits a long-standing assumption in bacterial chemotaxis—that Escherichia coli operate near the physical limits of chemical sensing imposed by the stochastic arrival of molecules at their receptors. Using an information-theoretic framework combined with single-cell measurements of chemotaxis signaling, the authors directly compare the information available from ligand arrival events to the information actually encoded by the cell’s signaling network. They find that E. coli acquire orders of magnitude less information than allowed by physical limits due to large, internally-generated fluctuations in signal processing. As a result, bacteria climb chemical gradients far more slowly than an ideal swimmer could. These findings overturn a classic view of chemotactic optimality and highlight the role of biological constraints, rather than physics alone, in shaping the design of sensory systems.